Read part 1 right here.

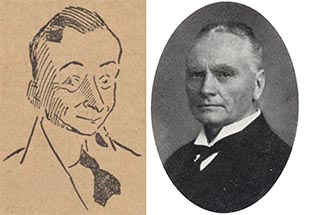

Svasse Bergqvist and his father, director general Bengt J:son Bergqvist. Svasse Bergqvist and his father, director general Bengt J:son Bergqvist.

Image sources: drawing from Svenska Dagbladet 31 August 1920 and photograph from Kristianstads nation i Lund 1911–1930 (Lund 1930).

Svasse Bergqvist’s father, the school administrator, director general and minister for education Bengt J:son Bergqvist, was a man of principles and ideals. During his time as headmaster in Kristianstad, he had among his pupils a precocious literary talent, Fredrik Christoffersson, who had already started contributing articles to the press. When this came to headmaster Bergqvist’s attention, he summoned the youth and explained that he had nothing against the articles and their content in themselves, but rather against the newspaper in which they were published. According to the headmaster, the paper was a mouthpiece “for the empty radicalism of the capital, for destructive trends and superficial views” and it was regrettable that it “recruited support troops” in the “righteous Swedish countryside”. But the principal also declared himself willing to help his pupil find a better forum for his work, a Stockholm weekly magazine which was guaranteed to be an “impeccable publication”. The headmaster was even personally acquainted with the editor there and could pass the texts on to him. The young Christoffersson realised that, in practice, this would give the headmaster a chance to censor the articles ahead of publication, so he firmly declined the offer. Some time later, presumably at the headmaster’s behest, Christoffersson got a lower grade in conduct and chose to leave the school in protest, completing his upper secondary diploma as a private student in Lund.

At least, this is what we are led to believe from the account provided many years later by Christoffersson himself, in his autobiographical novel Storskolan (The big school) from 1940 (in which the young pupil is called Bertil and Bergqvist appears as “headmaster Nyman”). By then, Fredrik Christoffersson had long since changed his surname to Böök, had managed to become a professor of literary history in Lund 1920–24 and, not least, developed into Sweden’s most influential literary critic.

“Destructive trends and superficial views” – was this what Bergqvist senior would later see expressed in his son’s cabaret sketches and farce? What we do know is that his son’s activities in popular humour and skimpily attired stage antics could seem strange and downright unworthy of the family’s proud academic and clerical traditions to the paternal persona of the director general. According to one of Svasse’s showbusiness colleagues, his father allegedly said “Nothing will ever come of Jakob. He occupies himself with such peculiar things. He claims that he can make a living writing these broadside ditties or whatever they are called” (the colleague then added that this “was before the tax returns of Karl Gerhard, Noel Coward and others on the same work were known”). On at least one occasion, the father’s scepticism was expressed as open criticism. He rang up his son and informed him that he “offended the family name through his sloppy writing for various stage revues”. The timing of the criticism was not well chosen, however. As the head of the supervisory body for schools, Bergqvist senior was, at the time, under strong attack in publications including the Tidning för Sveriges läroverk (Journal of Swedish Secondary Schools), so Svasse responded to his father’s criticism by stating:

“It is perfectly clear to anyone following the debate in the newspapers just now that I have a much higher reputation than you, father”.

A jocular villa-owner on record

The relationship between father and son was not so bad as to prevent the magazine Scenen from reporting in 1927 that the “director general of the supervisory body for schools” was spotted among guests gathered at Svasse Bergqvist’s home to congratulate him on his 40th birthday, although perhaps not primarily to “thank the author on behalf of the Schools Authority for his contributions to the schooling of youth”. The birthday festivities took place in the revue director’s own villa in Saltsjö-Duvnäs which, judging from the press’s interest in the house, was probably a recent acquisition. A few issues later, the same magazine was able to announce that, as a villa owner, Svasse subjected his neighbours to various pranks which can almost be described as student high-jinks:

On the big plot that belongs to the beautiful villa, there are a number of small fir trees that Mr Bergqvist decorated on Midsummer Eve with flags and garlands. Passers-by could not help laughing at the idea. The temperature was rather low, after all, on Midsummer Eve, so thoughts of winter were not far off. Furthermore, Mr Bergqvist has obtained a couple of large, beautiful white geese from Skåne and on Midsummer Eve he went out for a little walk in the community with his white geese. People he encountered probably looked a little astonished, as it is not often one meets farmhands herding geese around these parts. However, revue authors, whose job is to deal with everything, should be considered suited for such activities. Mr Bergqvist managed excellently in his role and came home with the waddling creatures quite unscathed.

That Svasse was able to buy a villa despite his subordinate and probably modestly paid position in the prison system could be seen as an indication that his activities in the entertainment world were better remunerated. However, it could also be seen as an expression of a certain financial carelessness, and Svasse’s potential to show such a tendency is something I will get back to further on. Perhaps the villa in Saltsjö-Duvnäs was acquired in the same way as the house in one of Svasse’s revue sketches from 1930, “Egen härd, guld värd” (“A hearth of your own is a treasure”) with Thor Modéen and Gösta Lycke. In the sketch, Modéen has bought a “hovel” (and virtually everything else he owns) on hire purchase: “32 000 quid – 32.50 up front and 15 per month”. The apparently good deal has its downsides, however. When Gösta Lycke, as the guest, is to go upstairs to “sleep on the top floor” it turns out that the whole upper floor is missing. “Well darn it!”, observes Modéen, “I haven’t kept up with my repayments, so they came to take it away this morning!”

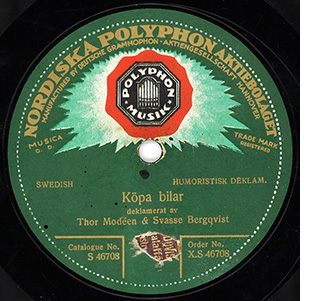

Plenty of sketches written by Svasse Bergqvist have been preserved on records and what’s more, the author himself performs on a handful of them, thereby leaving posterity with a chance to hear his voice. Usually, Bergqvist plays the “straight man” in dialogues with the popular Thor Modéen, who, thanks to comic timing and an ability to improvise, does his best to make the (admittedly) rather simple jokes work. Such as this example from the introduction to the number entitled “In the hat shop” (1926):

Modéen: Hello Fredrik! I would like a new spring hat.

Bergqvist: Yes, good day, good day! Is it for yourself?

Modéen: No, it’s for my brother.

Bergqvist: I see, what size?

Modéen: One metre eighty-four.

Bergqvist: No, I mean his head.

Modéen: Oh, his head. Yes, it’s very bad, it’s the worst in the whole family.

”Buying cars”, one of the dialogue recordings Svasse Bergqvist made together with comedian Thor Modéen. ”Buying cars”, one of the dialogue recordings Svasse Bergqvist made together with comedian Thor Modéen.

Image source: private collection.

Success for a less close-knit author duo

In its way, Svasse’s appearance on record is unique in that – apart from his performances as master of ceremonies in the very early stages of his career – he virtually never seems to have put himself on stage. Otherwise, during his years as a revue creator, he tried his hand at most tasks: besides writing scripts and song lyrics, he was also often responsible for directing the show, in particular in the early years, and at times he was also his own theatre director. As the 1920s went on, however, Svasse seems to have chosen a gradually less demanding and ominpotent role in his own productions. Not only did he write fewer new revues per year; Svasse also chose to focus on the manuscript itself, staying away from stage direction as well as most of the composition of song lyrics.

As a rule, the latter task went to the prolific song-writer Karl-Ewert Christenson, better known by his first name alone. Karl-Ewert was only a year younger than Svasse and like him, born in Lund, so it is not impossible that the future collaborators might already have met as children. However, Karl-Ewert never studied at the University, travelling to Stockholm instead where he studied at a business school and worked in a bank before getting sucked into the entertainment industry, where he delivered texts to both Ernst Rolf and Karl Gerhard. His collaboration with Svasse seems to have started with the revue “Come over here” in 1921, thereafter covering at least eight further productions. Yet the collaborative atmosphere between the two gentlemen was not always optimal, at least if we are to believe Kar de Mumma, who had a small hand in some of these productions:

"When Karl-Ewert’s songs were presented at a dress rehearsal, Svasse Bergquist left the theatre. And when Svasse’s sketches were played, Karl-Ewert disappeared. One day, Thor Modéen read one of my monologues, at which point both of them left."

Both gentlemen’s lack of coordination did not prevent one of their collaborations from becoming one of the real peaks of Bergqvist’s career in entertainment, however. It was the revue “Stockholm becomes Stockholm” at the Vasa theatre in autumn 1930. In it, Svasse & Co had a star-studded ensemble with already established artists such as Thor Modéen, Dagmar Ebbesen and Calle Hagman, but they had also managed to attract a completely new star from competitor Karl Gerhard: a singing 23 year-old named Zarah Leander (a “steal” that Karl Gerhard would allude to in his cabaret song “The more beautiful I become” in which Svasse is also mentioned). The revue was played 110 times and even the usually sceptical press was rather enthusiastic about it. Dagens Nyheter called the revue “a bull’s eye – or close” with “speed and verve […] over the whole thing from the very beginning” and in Ord och Bild, the reviewer Carl G Laurin praised the performance, not least, of Zarah Leander.

It was through this revue that Zarah Leander got her first hit. Most of the songs, including the show’s title tune “Stockholm becomes Stockholm”, were written by Karl-Ewert, but at least one of them bore Svasse’s signature. It was the Swedish version of Marlene Dietrich’s popular song “Ich bin von Kopf bis Fuß auf Liebe eingestellt”, which in Svasse’s translation became “Jag är från topp till tå ett kärleksstundens barn” (“From top to toe, I am a child of love”). In the same work, Svasse also wrote the lyrics to Leander’s film debut, the song “Demonen” (also known as “Jag vet vad ingen annan kvinna vet” – “I know what no other woman knows”), performed in the film Dantes mysterier (Dante’s mysteries) which premiered in 1931.

The prisoners’ friend gets an acquaintance in the slammer

Two years after “Stockholm becomes Stockholm”, the last Svasse show, “Syndare i sommarsol” (“Sinners in the summer sun”), was put on stage. It ran for fewer than half the performances there had been for the hit show two years previously. We cannot be sure whether this put Svasse off writing any more revue shows after that one. Another possible reason for the drop in his activities as an entertainer might simply have been that he was busier in his day job. From his initial position (as of 1916) as a mere assistant at Stockholm prison, he had gone on to a central assistant’s position in the prison system administration in 1922 but, during the 1930s, this post was combined at times with being the warden’s assistant at the central prison in Långholmen.

The latter assignment seems in practice to have meant being the acting prison warden. At any rate, Svasse’s showbusiness colleagues seem to have perceived him as such. For example, the popular singer Sven-Olof Sandberg wrote in a later book how the “the genial prison director from Skåne, notary Svasse Bergquist” from his prison office “pottered about amicably with his prisoners, whom he called ‛the boarders’”. Another colleague from the entertainment world who testified to Svasse’s relaxed relationship with the prisoners is the previously mentioned Kar de Mumma. He recounted how, on a visit to the prison, he “played […] poker with Svasse Bergquist, Lili Ziedner and a man jailed for grievous bodily harm, a friendly and timid person”!

A third acquaintance from the entertainment business went so far as to call the warden’s assistant Bergqvist “the prisoners’ friend”. However, the person in question had personal reasons for saying this: he was the scandal-prone songwriter and singer Johnny Bode, who was himself detained in one of Långholmen’s cells in the summer of 1936. Having been involved in an amateurish counterfeit cheque affair, he was there waiting for a mental examination when “a familiar, grizzled face” looked into the cell. It was Svasse, who entered with a cheery greeting, adding: “To think that you didn’t get away with it. It was only a trifling matter”.

Bode never forgave society or the doctors who examined him for the way they treated him during his time in prison; in contrast, he remembered Svasse’s treatment of him with warmth. Bode recounted how Svasse would regularly come and “fetch me, we wrote revue pieces at the prison’s grand piano up in the assembly hall. A couple of them came up for New Year in Kardemumma’s revue with Björn Hodell at Södran theatre”. Warden’s assistant Bergqvist apparently also enabled Bode to swap prison food for “deliveries from the finest restaurants” from time to time.

Bode also wrote in his memoirs that “[w]e have written innumerable things together since then, Svasse and I” and indeed the meeting at Långholmen seems to have been followed by a period of shared creativity. Two years later, in 1938, no less than eight different popular melodies were published, jointly composed by both gentlemen, in a total of twelve different recordings with different record companies, of which several featured vocals by Bode himself. The best known of these is probably “Den röda pelargonian” (“The Red Geranium”), which Bode also sang in the short film Musik och teknik (Music and Technology) the same year.

Only son – but not the only heir

Unusually for someone of his generation, Svasse Bergqvist was a child of divorced parents. They – the son of a parish priest and the daughter of a bishop – had separated as early as 1898 when Svasse was eleven years old; something which would have caused a bit of a scandal in the bourgeois-academic circles of Lund at the time. Both parents remarried fairly shortly thereafter, but as far as I have been able to determine, no further children were born from these new marriages, and Svasse thereby remained what he was to begin with: an only child.

One could imagine that, in time, Bergqvist junior would have inherited a significant amount from each of his parents, but things didn’t really work out that way. By the time of her death in 1910, his mother had certainly made her son her “only heir to a valuable estate”, but that will had clearly been contested by her second husband, the botanist, journalist and founder of the Lund philatelic association Ernst Ljungström, and it took until the end of 1934 for a court to establish that Svasse was “the rightful owner” of the estate.

Bengt Bergqvist (centre) as a jubilee doctor in Lund in 1935. Bengt Bergqvist (centre) as a jubilee doctor in Lund in 1935.

Image source: photo by Per Bagge (cropped) in the Lund University Library collections.

At that time, Svasse’s father was still alive and apparently enjoying good health into old age. In late spring of 1935, he travelled down to Lund to be honoured as a jubilee doctor (in what was in fact his third doctoral degree conferment; besides earning a PhD in 1884, he had also been awarded an honorary doctorate in theology in 1918). In a group photograph of the graduands, he appears stiff and straight-backed – despite the many medals weighing down his tailcoat – in the centre of the picture. Six months earlier, he had written his will, from which one can infer that he did not find his son’s management of affairs to be equally straight and honourable. From Svasse’s share of his father’s estate, previous loans were first to be deducted, and the direct inheritance was to be limited to 5 000 crowns in cash and the “bedlinen, bedclothes, tablecloths, etc.” that he considered to be “of use to him”. The testator had also specified the latter point with the hope that “such items were not to be taken by him merely with the aim of selling them” (could Svasse have done just that with his inheritance from his mother?). With a few other exceptions, the rest of the estate – subsequently valued at just over 50 000 crowns after tax (more than 1.5 million crowns at today’s value) – was to go into a fund to be administrated by the Odd Fellow Order, to finance the international study trips of the order’s members to “learn about social welfare institutions”. However, during a transition period, parts of the fund’s proceeds were to be distributed to a number of living persons, among whom Svasse, the son, was to receive one fifth for as long as he lived. Through these small annual payments (which would make up most of his statutory share of the inheritance) his father probably hoped to prevent wasteful excesses on the part of his son.

Still, a year or so later, Bengt Bergqvist made an addendum to his will. In it, he observed that “to my great joy, I perceive that my dear son […] has recently dedicated himself with greater seriousness to caring for his affairs”. As a reward, all the debts receivable by the estate were cancelled and the 5 000 crowns were doubled to 10 000, in addition to which Svasse was to receive half the value of his father’s house in Bromma. Finally, his share of the proceeds from the fund was increased to two fifths. The change came at the last minute from Svasse’s perspective: less than one year later, on 19 August 1936, his father passed away.

A pleasant way of writing a screenplay

Perhaps the combined inheritance from his father and mother made Svasse Bergqvist fairly financially independent after all. At any rate, in the early 1940s, when he was not yet 55 years old, he chose to resign from the prison system. Instead, he opened some form of independent legal practice and thereafter sometimes gave himself the title of “lawyer” in the press. Concerning Bergqvist’s non-legal activities, Dagens Nyheter already observed on his 50th birthday in 1937 that “[h]e has in recent years abandoned his theatrical activities, but still maintains a lively interest in the theatre”. However, this was not the end of Svasse’s active contributions to the entertainment sector. In 1945, he tackled a genre which, with the exception of the odd song lyric, was completely new to him – film – in cooperation with another native of Skåne. More specifically, an extremely well-known and popular figure: Edvard Persson.

In the years leading up to the collaboration with Svasse, Persson had enjoyed great success with two more culturally sophisticated films based on literary works: Livet på landet (Life in the countryside) and När seklet var ungt (When the century was young). Now the idea was to involve him in an even more ambitious project: a film version of Gogol’s The Government Inspector – to be made in colour, on location in the Soviet Union! The whole project was abandoned due to the Soviet authorities’ refusal to permit filming, so a new film idea was needed immediately, and this was where Svasse came into the picture as a screenplay writer in tandem with Edvard himself.

The screenplay, which was given the title Den glade skräddaren (The Happy Tailor), was written in Persson’s villa in the Stockholm district of Stora Essingen. Besides the gentleman of the house and Svasse, the writing sessions were attended by a 22 year-old script girl who acted as secretary and, on the basis of her account, Persson’s biographer Pontus Brandstedt described how the work proceeded:

Edvard, Svasse and the script girl sit at the dining table. She taps away on the typewriter. They sit on the sofa, smoke, have a drink, discuss, find even more witty repartee, whims, scenes, she taps away. Actors? Edvard has a few who are to be part of the project and the lovely Gyllenhammar could well pass as my adult daughter? Children! Five? Six? Dalkullan [Persson’s housekeeper?] serves the food, Mim [Persson’s wife] sneaks past and wonders whether coffee at half past five would be suitable. She taps away. Edvard strokes the dog.

In other words, the work process does not seem to have been too unpleasant. Nor should it have been too demanding with regard to coming up with a basic plot. Faithful to his habit – it is tempting to say – Svasse had indeed chosen to base the story on a foreign work, although it was not described more specifically in the film’s official programme than “based on an idea from abroad”. According to the Swedish film database, a large part of the film appears to be “very liberally borrowed” from the German comedy Borgmästarinnan badar (The Bath in the Barn) (1943). Once again, one is reminded of Ernst Rolf’s nasty song lyrics (see Part 1) about Svasse’s revues primarily being written abroad …

The interior scenes in The Happy Tailor were filmed in the Sundbyberg studio of Europafilm, but the outdoor scenes were filmed on location in Skåne, mainly in Norrvidinge. I don’t know to what extent Svasse was present for the filming, but if he was, he may have had the opportunity to meet another old Lund lawyer who ended up in showbusiness. Carl Deurell, who played the mayor in the film, had studied law in Lund in the 1890s but had changed course early on to become an actor, with his own theatre troupe for many years. In that capacity, Deurell was behind the first ever performance of a play about another Lund lawyer (albeit fictitious): Sten Stensson Stéen from Eslöv.

For those who would like to view Svasse Bergqvist’s only foray into screenplay writing, The Happy Tailor has been available on DVD since last year.

The cover of Europafilm’s advertising brochure in connection with Svasse and Edvard Persson’s film The Happy Tailor. The cover of Europafilm’s advertising brochure in connection with Svasse and Edvard Persson’s film The Happy Tailor.

Image source: Lund University Archive (Torsten Jungstedt collection).

An absolutely unknown name

After his efforts for Europafilm, the darkness of oblivion slowly began descending on Svasse Bergqvist. Occasionally, he would still appear in newspaper columns, but it was often merely about his participation in some radio talk show or a lecture to some association, based on his memories from the theatre, the prison system or old Stockholm in general. From time to time, he also wrote letters to the editor; then too, usually on some subject related to bygone days. That he gradually became a person whose future lay behind him will have become painfully obvious to him, if not earlier, then in autumn 1957, when he applied for accommodation at Höstsol. Höstsol – Autumn Sun – was a home for the elderly, established in 1918 and specially reserved for “theatre people”. You could think that a person who, over a decade and a half, had produced more than thirty revues and farces and had for certain periods also directed a theatre would be the perfect candidate for a room there. Nevertheless, the board rejected “Mr Bergquist’s application, as he could not be considered as having been sufficiently connected to the theatre to be granted entry”.

If even his former colleagues in showbusiness didn’t remember the breadth of Svasse’s stage efforts, how could the general public be expected to do so? “For the current generation, the name of Svasse Bergqvist is absolutely unknown” observed Svenska Dagbladet in a short text in connection with his 70th birthday. It was a birthday feature which almost sounded more like an obituary, and the fact is that the newspaper re-used large parts of it verbatim two and a half years later when Jacob Wilhelm Constantin B:son ”Svasse” Bergqvist, LLB., really did die on 21 December 1959.

“You want dream images, that entice and caress”

When Svasse Bergqvist is mentioned nowadays (if it happens at all) it is as a secondary figure; someone who flits past in the periphery of a story whose protagonist is someone else, better known to posterity – someone like Ernst Rolf, Carl Brisson, Jules Sylvain, Birger Sjöberg, Zarah Leander or Edvard Persson. But if you look at the role actually played by Bergqvist at the time – in Swedish showbusiness during the three first decades of the 1900s – you realise that he was actually quite often the central figure at the time. That he was the man who ensured the dsitribution of a daily dose of humour and glamour, mainly to the inhabitants of Stockholm but also (through records, sheet music and tours) to Swedes in general; a man who offered people a moment of relaxing escape from everyday life. Or as Svasse himself expressed the function of the lighter perfoming arts in the poem “Cabaret” in 1916:

When evening comes, the senses grow heavy

And the strong fist of reality loosens its grip for a while,

You long to forget, you want to sing,

And find an extension of your tired self.

You want melodies, wonderful, gentle

Tunes from the hidden life,

You want dream images, which entice and caress

In these thickets invisible in everyday life,

A strange note, like the sound from a grammophone.

Chrysanthemums and white orchids

On the silk lapels of tail coats,

A powdered cheek, a song with stale ideas

About love’s ebb and flow.

A serenade of plaintive strains from the cello,

A banjo dance from warmer latitudes,

A poem about undeserved happiness –

All the world’s a stage

When seen in the footlights – yes, such is it,

A cliché from melody to idea,

This very art, that we call cabaret.

Fredrik Tersmeden

Archivist

Lund University Archives

|